If you’ve been following me for any length of time (and a thousand blessings upon your home and camels if that’s the case) you have heard me refer to an odd ritual involving a specific brand of rye whiskey, a particular cigar, and my writing. Since a couple of you have asked me about it, here’s the explanation.

I have never been very good at “treating myself.” This is partly due to spending most of my life broke as a joke, and mostly due to a healthy dose of Baptist guilt leftover from my childhood. While happy to partake in the celebrations and victory laps of others, I tend not to do the same for myself. It’s a thing.

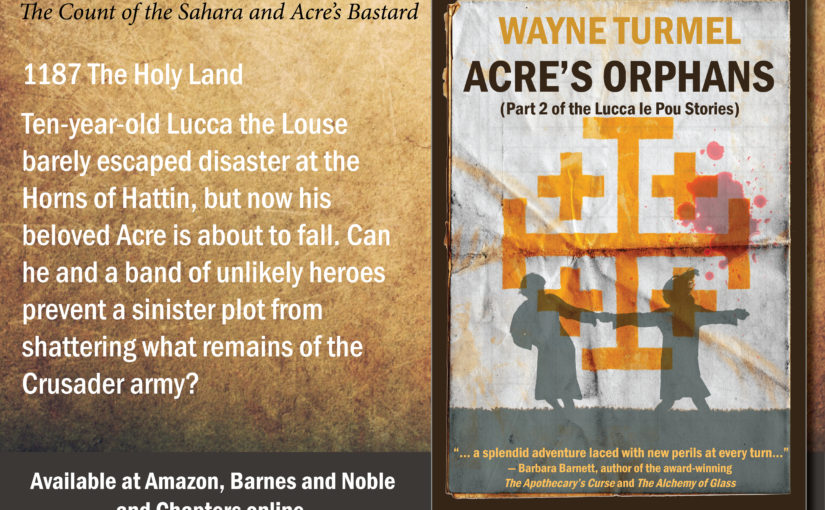

But when I set out to write my first novel which eventually became Count of the Sahara (original title, Pith Helmets in the Snow. This is why publishers and editors get a voice in such decisions–to save authors from themselves and blessings on Erik at The Book Folks) I was fifty-two years old and not sure I could do it. I promised myself some kind of small reward if/when I ever finished the damned thing.

Having neither the money nor the spleen to do anything big and splashy, I thought a shot of something special would do nicely. But what?

Well, the book takes place during Prohibition here in the US. Byron de Prorok (you have read it, right?) one night gets his hand on some bootleg hooch from Templeton, Iowa and he and Willy get rip-roaringly drunk. Templeton rye was considered the best of the American rye whiskeys by Al Capone.

Years later the descendants of those folks have re-issued Templeton as a small brand. I saw it on a pub shelf one day and decided that if the damned book ever got finished, I would celebrate with a shot of Templeton Rye.

I did. It was yummy. It’s also a bit more expensive than the usual stuff we keep at home, so it’s for special occasions. It’s reserved for:

- Finishing first drafts (applies only to novels and non-fiction books)

- Finishing final drafts (ditto)

- Acceptance by a publisher (also applies to short stories)

- The day the boxes arrive with the Advanced Reading Copies.

I also celebrate with a cigar. Yes, I know. As I explained to my doctor, I’ve never smoked a cigarette in my life, I smoke a single cigar less than once a week, and I’m fully aware that taking a plant, setting it on fire, and putting it in my mouth is probably less than good for me. I also know that those with no visible vices are the people you can’t trust.

My smoke of choice, for what it’s worth, is La Aroma de Cuba El Jefe. Not a particularly fancy-schmancy stick but it’s the size, duration, and strength I like. Sue me.

Oh, and I generally do this alone. Solo. Just me. This celebration is for me and me alone, and today’s the day.

I have finished the first draft of Johnny Lycan. It’s unlike anything you’ve read from me. It’s decidedly not historical fiction, and some of you are going to hate it (or at least that’s what the gremlins in the back of my head are telling me) although I am very fond of the damned thing and I believe it will find a large audience.

If you need me today, I’ll be on the deck, in the shade because it’s a hundred freaking degrees out, celebrating and indulging my inner Hemingway. Now you know.